Here are three methods of street illumination in vogue in this country gas, oil and electricity.

Here are three methods of street illumination in vogue in this country gas, oil and electricity.

These are susceptible of sub-division, as, gas into manufactured and natural; oil into kerosene, naphtha and gasoline; electricity into arc and incandescent. Manufactured gas is used exclusively in many places where long contracts have not expired, or where the authorities have not been sufficiently enterprising to adopt- electricity, or have been unduly prejudiced against it. Natural gas is, of course, in use only where the circumstances of location make it available, and the country contiguous thereto. It is not a good illuminant on account of the intense heat which it emits.

Oil is generally in use in small places where the establishment of gas works would be unprofitable, or the rays of electricity have not penetrated. Street illumination in many of the large cities oils are still in use in the outlying portions. Electricity has come to be recognized as the successor of all these out-door illurninants, and its fight for place has not been to any degree more earnest than has the battle between arc and incandescent lighting. The former is the better intrenched, because it antedated the latter, but the progress made by “the incandescent light has reached that point where it now unreservedly asserts itself as a competitor, and municipalities should in the future consider both in their discussions. Heretofore the incandescent lamp has been regarded more as an interior light, and its chief competitor for street illumination was gas.

The entire question of street illumination, aside from the various considerations entering into the adoption of any system, is one of the distribution of light. The advocates of the arc light, the multiple arc and the incandescent will each aver that his particular system will give the best distribution, and he will be prepared to prove it. It will resolve itself in the mind of the average layman like he who ” could be happy with either were t’other dear charmer away.”

In considering the distribution of light one should not compute the total candle power of a given territory, and raise or lower the lamps until an equal distribution of the light is obtained. There will be alternate dark arid light spots in that case. The property owner living in the center of a block is as much entitled to light as he who lives on or near the corner.

The effect of light on crime will not be so perceptible if the alleys and back-yards are neglected. To get an equal distribution of light the city should first determine where it wants light and should then study the different systems as a means of putting it there. As someone has said, “the experience of practical users is more valuable in enabling one to determine what to buy, than scientific tests or anybody’s guarantee.”

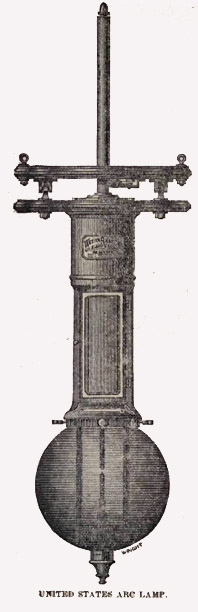

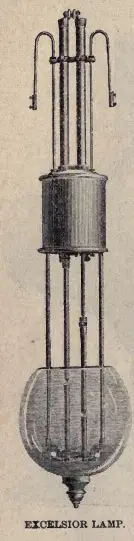

The attention of the reader is therefore called to that which here follows. Three methods of placing arc lamps for street lighting are extensively used. These are:

The attention of the reader is therefore called to that which here follows. Three methods of placing arc lamps for street lighting are extensively used. These are:

First. Placing lamps upon poles.

Second. Placing lamps over intersection of streets.

Third. Placing lamps upon towers.

The first method, that of placing lamps upon poles, has but one advantage cheapness of first cost while it has many disadvantages; mainly from the fact that the pole can be placed upon one side of the street only, the light is unequally distributed, and, where shade trees exist, only the opposite side of the street can be lighted. A serious disadvantage, and one that deserves more attention than it receives, is the cost of carbon trimming. The trimmer requires time to climb to the lamp, and time is money and climbing dangerous. It will, therefore, be seen that, while the first cost is much cheaper, in the end, pole lighting costs more money than any other.

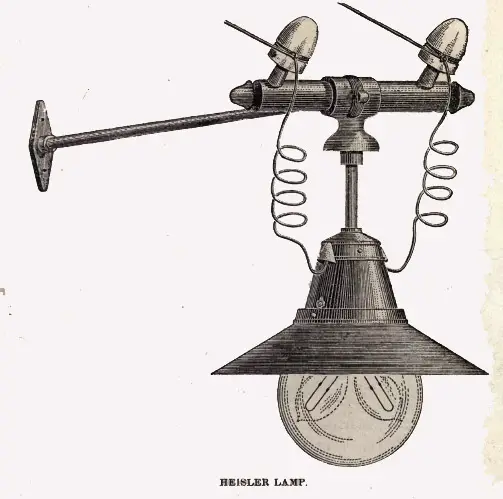

In some places where pole lights are in use the lamps are simply stuck upon crooked and ill-shaped wooden poles, giving an appearance of shiftlessness that speaks ill of the system and of the company that puts such unsightly objects on the streets. The cut of a street-light here shown illustrates how a pole light can be placed neatly, and with but a slight additional cost over the slip-shod method referred to.

The second method, that of placing lamps over the intersections of streets, is the best method when low arc lighting is desired. It has many decided advantages over the pole method. By placing a lamp over the intersection of streets, you place the lamp where it can do the most possible good, as it can light the streets equally in four directions a distance of about 400 feet radius of the lamp. The lamp is far enough away from shade trees to allow its rays to penetrate underneath them and thoroughly light the sidewalk.

Street illumination lamps should be at least thirty-five, feet from the surface of the street. There are four ways by which lamps can be placed in this position. One is to erect two poles upon diagonally opposite corners of the street, and connect them at the top with a twisted wire cable. The lamp is hung on a pulley on the center of this cable; a line is attached and the lamp is drawn in to the top of the pole for trimming.

Another method is that of an iron pulley fastened to the center of a cable, the lamp being lowered to the center of the street. During the extremely cold weather of winter, the cables and cords are liable to become coated with ice and the apparatus fail to work.

Street Illumination source: Whipple, F.H., 1888, Municipal Lighting, Free Press Print, USA Michigan