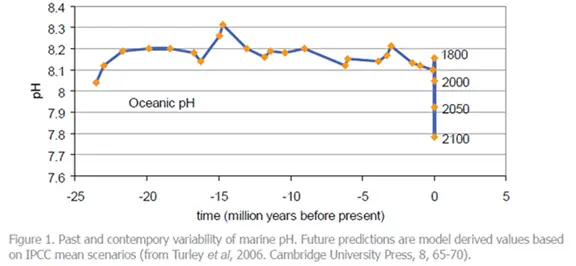

Ocean acidification: The scientific community are becoming increasingly worried about this development, which is a direct result of the increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. Absorption rates can vary, but approximately 40% of global anthropogenic (human) carbon dioxide emissions remain in the atmosphere, the rest is taken up by vegetation on land or absorbed by the world’s oceans, currently in about equal proportions. Ocean acidification caused by increased carbon dioxide uptake by the oceans is expected to reduce surface ocean pH by 0.3 – 0.5 units over the next century, which would be the largest change in pH to occur in the last 20-200 million years.

We know that the carbon dioxide is a direct result of burning fossil fuels, as unlike the make up of living organisms, fossil fuels contain little or none of the radioactive form of carbon, that is, the carbon 14 isotope, which has eight neutrons in the nucleus rather than the usual six. Fossil fuels also display a unique ratio of the two stable isotopes of carbon (carbon 12 and 13). The combustion of these fuels thus leaves a distinctive isotopic signature in the atmosphere. So no one can question where the growing surplus of carbon dioxide comes from.

The Royal Society of London published a report Ocean acidification in 2005, which summarised the salient points:

1. Carbon dioxide from the atmosphere dissolves in the ocean making it more acidic.

2. This is inevitable with high carbon dioxide, no fancy models are involved.

3. The oceans have already become 30% more acidic than before fossil fuel burning started.

4. Acidification will kill corals, and destroy other marine life.

5. There has been no period like this in the past 2 million years.

Increases In Carbon Dioxide Leads To Ocean Acidification

There is equilibrium between atmospheric carbon dioxide and carbon dioxide (CO2) dissolved in seawater: as atmospheric levels increase, so do the levels of CO2 dissolved in the ocean waters, especially in the surface waters where most ocean life flourishes. Each day millions of tons of CO2 are dissolved in seawater, reacting to form carbonic acid (H2CO3). This reaction lowers the pH, which is indicative of rising acidity.

Evidence indicates that emissions of carbon dioxide from human activities over the past 200 years have already led to a reduction in the average pH of surface seawater of 0.1 units and could fall by 0.5 units by the year 2100. This pH is probably lower than has been experienced for hundreds of millennia and, critically, at a rate of change probably 100 times greater than at any time over this period. This is potentially disastrous as common marine organisms, such as the fish we use as food, may be unable to survive.

NOAA scientists (2006) have indicated that pH is decreasing and there are increases in dissolved inorganic carbon in surface waters over a large section of the north-eastern Pacific. “The pH decrease is direct evidence of ocean acidification in the Pacific Ocean,” said NOAA scientist Richard Feely. “These dramatic changes can be attributed, in most part, to anthropogenic CO2 uptake by the ocean over the past 15 years. This verifies earlier model projections that the oceans are becoming more acidic because of the uptake of carbon dioxide released as a result of fossil fuel burning.”

What Life Forms Will Be Affected?

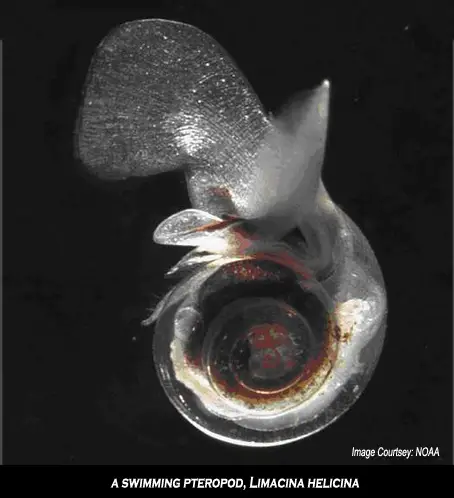

Some of the most abundant lifeforms that could be affected by ocean acidification are a type of phytoplankton called coccolithophorids, which are covered with small plates of calcium carbonate and are commonly found floating near the surface of the ocean (where they use the abundant sunlight for photosynthesis). Other important examples are planktonic organisms called foraminifera (which are related to amoeba) and pteropods (small marine snails).

The image above is a swimming pteropod, known scientifically as Limacina helicina. These free-swimming planktonic molluscs form a calcium carbonate shell made of aragonite. They are an important food source for juvenile North Pacific salmon and also are eaten by mackerel, herring and cod.

Experiments carried out at sea have shown that the shells of live pteropods dissolve when seawater reaches corrosive levels. Ocean acidification is detrimental to high-latitude ecosystems and highly acidic conditions could develop within decades, not centuries as suggested previously.

A fall in the numbers of pteropods could cause a chain reaction since they make up the basic food for organisms from zooplankton to whales, as well as for species that are important commercially, such as North Pacific salmon. For example, the plankton on which cod larvae feed would disappear, and the cod would then go too, and something else not linked heavily to the food chain – like jellyfish – will move into their niche in the ecosystem.

Coral Reefs, which are viewed as the ocean’s rain forests because of their amazing biological diversity are also threatened by acidification. About a quarter of all ocean species spend at least part of their life cycle on reefs. Calcium carbonate is essential for the development of coral, and it also provides a habitat for deep-sea fish, eels, crabs, sea urchins, etc, while the external skeleton of sea urchins is also directly threatened by acidification.

Coralline algae (algae that also secrete calcium carbonate and often resemble corals) also contribute to the calcification of many reefs. The Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia, is the largest biological structure in the world and is simply the accumulation of generation after generation of coral and coralline algae. Marine scientist from Australia Queensland University, say that coral cover will decrease to less than five percent on most reefs by the middle of the century under even the most favourable assumptions.

Skeletal records of corals in the Great Barrier Reef show that calcification has declined by 14.2% since 1990(1). The data suggest that such a severe and sudden decline in calcification is unprecedented in at least the past 400 years.

This outcome is due to both sea temperatures rises, which bleaches coral , and rising ocean acidity. (Warmer sea waters make corals suffer thermal stress; eventually making them bleach and die.)

It has been estimated that up to 80% of the coral coverage in the Caribbean has already been lost in the last 30 years (also affected by pollution and overfishing ).

Conclusion

Continuing along the path of burning fossil fuels and releasing millions of tons each day of carbon dioxide which is absorbed by the oceans, will have impacts on marine ecosystems that will be direct, profound and irreversible.

Ocean acidification is essentially irreversible during our lifetimes. It will take tens of thousands of years for ocean chemistry to return to a condition similar to that occurring at pre-industrial times (about 200 years ago). Our ability to reduce ocean acidification through artificial methods such as the addition of chemicals is unproven. These techniques will at best be effective only at a very local scale, and could also cause damage to the marine environment.

Reducing CO2 emissions to the atmosphere is the only practical way to minimise the risk of large-scale and long term changes to the oceans.

(1)De’ath G, Lough JM, Fabricius KE (2009, Declining coral calcification on the great barrier reef. Science, 323(116).